Behavioral economics

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Nudge theory |

|---|

Behavioral economics is the study of the psychological (e.g. cognitive, behavioral, affective, social) factors involved in the decisions of individuals or institutions, and how these decisions deviate from those implied by traditional economic theory.[1][2]

Behavioral economics is primarily concerned with the bounds of rationality of economic agents. Behavioral models typically integrate insights from psychology, neuroscience and microeconomic theory.[3][4]

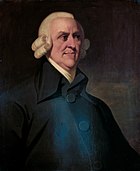

Behavioral economics began as a distinct field of study in the 1970s and 1980s, but can be traced back to 18th-century economists, such as Adam Smith, who deliberated how the economic behavior of individuals could be influenced by their desires.[5]

The status of behavioral economics as a subfield of economics is a fairly recent development; the breakthroughs that laid the foundation for it were published through the last three decades of the 20th century.[6][7] Behavioral economics is still growing as a field, being used increasingly in research and in teaching.[8]

History

[edit]

Early classical economists included psychological reasoning in much of their writing, though psychology at the time was not a recognized field of study.[9] In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith wrote on concepts later popularized by modern Behavioral Economic theory, such as loss aversion.[9] Jeremy Bentham, a Utilitarian philosopher in the 1700s conceptualized utility as a product of psychology.[9] Other economists who incorporated psychological explanations in their works included Francis Edgeworth, Vilfredo Pareto and Irving Fisher.

A rejection and elimination of psychology from economics in the early 1900s brought on a period defined by a reliance on empiricism.[9] There was a lack of confidence in hedonic theories, which saw pursuance of maximum benefit as an essential aspect in understanding human economic behavior.[6] Hedonic analysis had shown little success in predicting human behavior, leading many to question its viability as a reliable source for prediction.[6]

There was also a fear among economists that the involvement of psychology in shaping economic models was inordinate and a departure from accepted principles.[10] They feared that an increased emphasis on psychology would undermine the mathematic components of the field.[11][12]

To boost the ability of economics to predict accurately, economists started looking to tangible phenomena rather than theories based on human psychology.[6] Psychology was seen as unreliable to many of these economists as it was a new field, not regarded as sufficiently scientific.[9] Though a number of scholars expressed concern towards the positivism within economics, models of study dependent on psychological insights became rare.[9] Economists instead conceptualized humans as purely rational and self-interested decision makers, illustrated in the concept of homo economicus.[12]

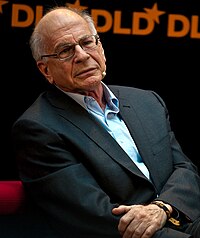

The resurgence of psychology within economics, which facilitated the expansion of behavioral economics, has been linked to the cognitive revolution.[13][14] In the 1960s, cognitive psychology began to shed more light on the brain as an information processing device (in contrast to behaviorist models). Psychologists in this field, such as Ward Edwards,[15] Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman began to compare their cognitive models of decision-making under risk and uncertainty to economic models of rational behavior. These developments spurred economists to reconsider how psychology could be applied to economic models and theories.[9] Concurrently, the Expected utility hypothesis and discounted utility models began to gain acceptance. In challenging the accuracy of generic utility, these concepts established a practice foundational in behavioral economics: Building on standard models by applying psychological knowledge.[6]

Mathematical psychology reflects a long-standing interest in preference transitivity and the measurement of utility.[16]

Development of Behavioral Economics

[edit]In 2017, Niels Geiger, a lecturer in economics at the University of Hohenheim conducted an investigation into the proliferation of behavioral economics.[8] Geiger's research looked at studies that had quantified the frequency of references to terms specific to behavioral economics, and how often influential papers in behavioral economics were cited in journals on economics.[8] The quantitative study found that there was a significant spread in behavioral economics after Kahneman and Tversky's work in the 1990s and into the 2000s.[8]

| 1979 Paper | 1992 Paper | 1974 Paper | 1981 Paper | 1986 Paper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1974-78 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1979-83 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| 1984-88 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1989-93 | 19 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3 |

| 1993-98 | 37 | 16 | 12 | 7 | 6 |

| 1999-2003 | 51 | 20 | 5 | 15 | 11 |

| 2004-08 | 80 | 48 | 18 | 15 | 16 |

| 2009-13 | 161 | 110 | 59 | 38 | 19 |

| Total Citations | 356 | 195 | 101 | 85 | 55 |

Bounded rationality

[edit]

Bounded rationality is the idea that when individuals make decisions, their rationality is limited by the tractability of the decision problem, their cognitive limitations and the time available.

Herbert A. Simon proposed bounded rationality as an alternative basis for the mathematical modeling of decision-making. It complements "rationality as optimization", which views decision-making as a fully rational process of finding an optimal choice given the information available.[17] Simon used the analogy of a pair of scissors, where one blade represents human cognitive limitations and the other the "structures of the environment", illustrating how minds compensate for limited resources by exploiting known structural regularity in the environment.[17] Bounded rationality implicates the idea that humans take shortcuts that may lead to suboptimal decision-making. Behavioral economists engage in mapping the decision shortcuts that agents use in order to help increase the effectiveness of human decision-making. Bounded rationality finds that actors do not assess all available options appropriately, in order to save on search and deliberation costs. As such decisions are not always made in the sense of greatest self-reward as limited information is available. Instead agents shall choose to settle for an acceptable solution. One approach, adopted by Richard M. Cyert and March in their 1963 book A Behavioral Theory of the Firm, was to view firms as coalitions of groups whose targets were based on satisficing rather than optimizing behaviour.[18][19] Another treatment of this idea comes from Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler's Nudge.[20][21] Sunstein and Thaler recommend that choice architectures are modified in light of human agents' bounded rationality. A widely cited proposal from Sunstein and Thaler urges that healthier food be placed at sight level in order to increase the likelihood that a person will opt for that choice instead of less healthy option. Some critics of Nudge have lodged attacks that modifying choice architectures will lead to people becoming worse decision-makers.[22][23]

Prospect theory

[edit]

In 1979, Kahneman and Tversky published Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk, that used cognitive psychology to explain various divergences of economic decision making from neo-classical theory.[24] Kahneman and Tversky utilising prospect theory determined three generalisations; gains are treated differently than losses, outcomes received with certainty are overweighed relative to uncertain outcomes and the structure of the problem may affect choices. These arguments were supported in part by altering a survey question so that it was no longer a case of achieving gains but averting losses and the majority of respondents altered their answers accordingly. In essence proving that emotions such as fear of loss, or greed can alter decisions, indicating the presence of an irrational decision-making process. Prospect theory has two stages: an editing stage and an evaluation stage. In the editing stage, risky situations are simplified using various heuristics. In the evaluation phase, risky alternatives are evaluated using various psychological principles that include:

- Reference dependence: When evaluating outcomes, the decision maker considers a "reference level". Outcomes are then compared to the reference point and classified as "gains" if greater than the reference point and "losses" if less than the reference point.

- Loss aversion: Losses are avoided more than equivalent gains are sought. In their 1992 paper, Kahneman and Tversky found the median coefficient of loss aversion to be about 2.25, i.e., losses hurt about 2.25 times more than equivalent gains reward.[25]

- Non-linear probability weighting: Decision makers overweigh small probabilities and underweigh large probabilities—this gives rise to the inverse-S shaped "probability weighting function".

- Diminishing sensitivity to gains and losses: As the size of the gains and losses relative to the reference point increase in absolute value, the marginal effect on the decision maker's utility or satisfaction falls.

In 1992, in the Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, Kahneman and Tversky gave a revised account of prospect theory that they called cumulative prospect theory.[25] The new theory eliminated the editing phase in prospect theory and focused just on the evaluation phase. Its main feature was that it allowed for non-linear probability weighting in a cumulative manner, which was originally suggested in John Quiggin's rank-dependent utility theory. Psychological traits such as overconfidence, projection bias and the effects of limited attention are now part of the theory. Other developments include a conference at the University of Chicago,[26] a special behavioral economics edition of the Quarterly Journal of Economics ("In Memory of Amos Tversky"), and Kahneman's 2002 Nobel Prize for having "integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty."[27]

A further argument of Behavioural Economics relates to the impact of the individual's cognitive limitations as a factor in limiting the rationality of people's decisions. Sloan first argued this in his paper 'Bounded Rationality' where he stated that our cognitive limitations are somewhat the consequence of our limited ability to foresee the future, hampering the rationality of decision.[28] Daniel Kahneman further expanded upon the effect cognitive ability and processes have on decision making in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow Kahneman delved into two forms of thought, fast thinking which he considered "operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control".[29] Conversely, slow thinking is the allocation of cognitive ability, choice and concentration. Fast thinking utilises heuristics, which is a decision-making process that undertakes shortcuts, and rules of thumb to provide an immediate but often irrational and imperfect solution. Kahneman proposed that the result of the shortcuts is the occurrence of a number of biases such as hindsight bias, confirmation bias and outcome bias among others. A key example of fast thinking and the resultant irrational decisions is the 2008 financial crisis.

Nudge theory

[edit]Nudge is a concept in behavioral science, political theory and economics which proposes designs or changes in decision environments as ways to influence the behavior and decision making of groups or individuals—in other words, it's "a way to manipulate people's choices to lead them to make specific decisions".[30]

The first formulation of the term and associated principles was developed in cybernetics by James Wilk before 1995 and described by Brunel University academic D. J. Stewart as "the art of the nudge" (sometimes referred to as micronudges[31]). It also drew on methodological influences from clinical psychotherapy tracing back to Gregory Bateson, including contributions from Milton Erickson, Watzlawick, Weakland and Fisch, and Bill O'Hanlon.[32] In this variant, the nudge is a microtargeted design geared towards a specific group of people, irrespective of the scale of intended intervention.

In 2008, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein's book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness brought nudge theory to prominence.[30] It also gained a following among US and UK politicians, in the private sector and in public health.[33] The authors refer to influencing behavior without coercion as libertarian paternalism and the influencers as choice architects.[34] Thaler and Sunstein defined their concept as:[35]

A nudge, as we will use the term, is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people's behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.

Nudging techniques aim to capitalise on the judgemental heuristics of people. In other words, a nudge alters the environment so that when heuristic, or System 1, decision-making is used, the resulting choice will be the most positive or desired outcome.[36] An example of such a nudge is switching the placement of junk food in a store, so that fruit and other healthy options are located next to the cash register, while junk food is relocated to another part of the store.[37]

In 2008, the United States appointed Sunstein, who helped develop the theory, as administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.[34][38][39]

Notable applications of nudge theory include the formation of the British Behavioural Insights Team in 2010. It is often called the "Nudge Unit", at the British Cabinet Office, headed by David Halpern.[40] In addition, the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit is the world's first behavioral design team embedded within a health system.

Nudge theory has also been applied to business management and corporate culture, such as in relation to health, safety and environment (HSE) and human resources. Regarding its application to HSE, one of the primary goals of nudge is to achieve a "zero accident culture".[41]

Criticisms

[edit]Cass Sunstein has responded to critiques at length in his The Ethics of Influence[42] making the case in favor of nudging against charges that nudges diminish autonomy,[43] threaten dignity, violate liberties, or reduce welfare. Ethicists have debated this rigorously.[44] These charges have been made by various participants in the debate from Bovens[45] to Goodwin.[46] Wilkinson for example charges nudges for being manipulative, while others such as Yeung question their scientific credibility.[47]

Some, such as Hausman & Welch[48] have inquired whether nudging should be permissible on grounds of (distributive[clarification needed]) justice; Lepenies & Malecka[49] have questioned whether nudges are compatible with the rule of law. Similarly, legal scholars have discussed the role of nudges and the law.[50][51]

Behavioral economists such as Bob Sugden have pointed out that the underlying normative benchmark of nudging is still homo economicus, despite the proponents' claim to the contrary.[52]

It has been remarked that nudging is also a euphemism for psychological manipulation as practiced in social engineering.[53][54]

There exists an anticipation and, simultaneously, implicit criticism of the nudge theory in works of Hungarian social psychologists who emphasize the active participation in the nudge of its target (Ferenc Merei[55] and Laszlo Garai[56]).

Concepts

[edit]Behavioral economics aims to improve or overhaul traditional economic theory by studying failures in its assumptions that people are rational and selfish. Specifically, it studies the biases, tendencies and heuristics of people's economic decisions. It aids in determining whether people make good choices and whether they could be helped to make better choices. It can be applied both before and after a decision is made.

Search heuristics

[edit]Behavioral economics proposes search heuristics as an aid for evaluating options. It is motivated by the fact that it is costly to gain information about options and it aims to maximise the utility of searching for information. While each heuristic is not wholistic in its explanation of the search process alone, a combination of these heuristics may be used in the decision-making process. There are three primary search heuristics.

Satisficing

Satisficing is the idea that there is some minimum requirement from the search and once that has been met, stop searching. After satisficing, a person may not have the most optimal option (i.e. the one with the highest utility), but would have a "good enough" one. This heuristic may be problematic if the aspiration level is set at such a level that no products exist that could meet the requirements.

Directed cognition

Directed cognition is a search heuristic in which a person treats each opportunity to research information as their last. Rather than a contingent plan that indicates what will be done based on the results of each search, directed cognition considers only if one more search should be conducted and what alternative should be researched.

Elimination by aspects

Whereas satisficing and directed cognition compare choices, elimination by aspects compares certain qualities. A person using the elimination by aspects heuristic first chooses the quality that they value most in what they are searching for and sets an aspiration level. This may be repeated to refine the search. i.e. identify the second most valued quality and set an aspiration level. Using this heuristic, options will be eliminated as they fail to meet the minimum requirements of the chosen qualities.[57]

Heuristics and cognitive effects

[edit]Besides searching, behavioral economists and psychologists have identified other heuristics and other cognitive effects that affect people's decision making. These include:

Mental accounting

Mental accounting refers to the propensity to allocate resources for specific purposes. Mental accounting is a behavioral bias that causes one to separate money into different categories known as mental accounts either based on the source or the intention of the money.[58]

Anchoring

Anchoring describes when people have a mental reference point with which they compare results to. For example, a person who anticipates that the weather on a particular day would be raining, but finds that on the day it is actually clear blue skies, would gain more utility from the pleasant weather because they anticipated that it would be bad.[59]

Herd behavior

This is a relatively simple bias that reflects the tendency of people to mimic what everyone else is doing and follow the general consensus.

Framing effects

People tend to choose differently depending on how the options are presented to them. People tend to have little control over their susceptibility to the framing effect, as often their choice-making process is based on intuition.[60]

Biases and fallacies

[edit]While heuristics are tactics or mental shortcuts to aid in the decision-making process, people are also affected by a number of biases and fallacies. Behavioral economics identifies a number of these biases that negatively affect decision making such as:

Present bias

Present bias reflects the human tendency to want rewards sooner. It describes people who are more likely to forego a greater payoff in the future in favour of receiving a smaller benefit sooner. An example of this is a smoker who is trying to quit. Although they know that in the future they will suffer health consequences, the immediate gain from the nicotine hit is more favourable to a person affected by present bias. Present bias is commonly split into people who are aware of their present bias (sophisticated) and those who are not (naive).[61]

Gambler's fallacy

The gambler's fallacy stems from law of small numbers.[62] It is the belief that an event that has occurred often in the past is less likely to occur in the future, despite the probability remaining constant. For example, if a coin had been flipped three times and turned up heads every single time, a person influenced by the gambler's fallacy would predict that the next one ought to be tails because of the abnormal number of heads flipped in the past, even though the probability of a heads occurring is still 50%.[63]

Hot hand fallacy

The hot hand fallacy is the opposite of the gambler's fallacy. It is the belief that an event that has occurred often in the past is more likely to occur again in the future such that the streak will continue. This fallacy is particularly common within sports. For example, if a football team has consistently won the last few games they have participated in, then it is often said that they are 'on form' and thus, it is expected that the football team will maintain their winning streak.[64]

Narrative fallacy

Narrative fallacy refers to when people use narratives to connect the dots between random events to make sense of arbitrary information. The term stems from Nassim Taleb's book The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. The narrative fallacy can be problematic as it can lead to individuals making false cause-effect relationships between events.[65] For example, a startup may get funding because investors are swayed by a narrative that sounds plausible, rather than by a more reasoned analysis of available evidence.[66]

Loss aversion

Loss aversion refers to the tendency to place greater weight on losses compared to equivalent gains. In other words, this means that when an individual receives a loss, this will cause their utility to decline more so than the same-sized gain.[67] This means that they are far more likely to try to assign a higher priority on avoiding losses than making investment gains. As a result, some investors might want a higher payout to compensate for losses. If the high payout is not likely, they might try to avoid losses altogether even if the investment's risk is acceptable from a rational standpoint.[68]

Recency bias

Recency bias is the belief that of a particular outcome is more probably simply because it had just occurred. For example, if the previous one or two flips were heads, a person affected by recency bias would continue to predict that heads would be flipped.[69]

Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to prefer information consistent with one's beliefs and discount evidence inconsistent with them.[70]

Familiarity bias

Familiarity bias simply describes the tendency of people to return to what they know and are comfortable with. Familiarity bias discourages affected people from exploring new options and may limit their ability to find an optimal solution.[71]

Status quo bias

Status quo bias describes the tendency of people to keep things as they are. It is a particular aversion to change in favor of remaining comfortable with what is known.[72]

Connected to this concept is the endowment effect, a theory that people value things more if they own them - they require more to give up an object than they would be willing to pay to acquire it.[73]

Behavioral finance

[edit]Behavioral finance[74] is the study of the influence of psychology on the behavior of investors or financial analysts. It assumes that investors are not always rational, have limits to their self-control and are influenced by their own biases.[75] For example, behavioral law and economics scholars studying the growth of financial firms' technological capabilities have attributed decision science to irrational consumer decisions.[76]: 1321 It also includes the subsequent effects on the markets. Behavioral Finance attempts to explain the reasoning patterns of investors and measures the influential power of these patterns on the investor's decision making. The central issue in behavioral finance is explaining why market participants make irrational systematic errors contrary to assumption of rational market participants.[1] Such errors affect prices and returns, creating market inefficiencies.

Traditional finance

[edit]The accepted theories of finance are referred to as traditional finance. The foundation of traditional finance is associated with the modern portfolio theory (MPT) and the efficient-market hypothesis (EMH). Modern portfolio theory is based on a stock or portfolio's expected return, standard deviation, and its correlation with the other assets held within the portfolio. With these three concepts, an efficient portfolio can be created for any group of assets. An efficient portfolio is a group of assets that has the maximum expected return given the amount of risk. The efficient-market hypothesis states that all public information is already reflected in a security's price. The proponents of the traditional theories believe that "investors should just own the entire market rather than attempting to outperform the market". Behavioral finance has emerged as an alternative to these theories of traditional finance and the behavioral aspects of psychology and sociology are integral catalysts within this field of study.[77]

Evolution

[edit]The foundations of behavioral finance can be traced back over 150 years. Several original books written in the 1800s and early 1900s marked the beginning of the behavioral finance school. Originally published in 1841, MacKay's Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds presents a chronological timeline of the various panics and schemes throughout history.[78] This work shows how group behavior applies to the financial markets of today. Le Bon's important work, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, discusses the role of "crowds" (also known as crowd psychology) and group behavior as they apply to the fields of behavioral finance, social psychology, sociology and history. Selden's 1912 book Psychology of The Stock Market applies the field of psychology directly to the stock market and discusses the emotional and psychological forces at work on investors and traders in the financial markets. These three works along with several others form the foundation of applying psychology and sociology to the field of finance. The foundation of behavioral finance is an area based on an interdisciplinary approach including scholars from the social sciences and business schools. From the liberal arts perspective, this includes the fields of psychology, sociology, anthropology, economics and behavioral economics. On the business administration side, this covers areas such as management, marketing, finance, technology and accounting.

Critics contend that behavioral finance is more a collection of anomalies than a true branch of finance and that these anomalies are either quickly priced out of the market or explained by appealing to market microstructure arguments. However, individual cognitive biases are distinct from social biases; the former can be averaged out by the market, while the other can create positive feedback loops that drive the market further and further from a "fair price" equilibrium. It is observed that, the problem with the general area of behavioral finance is that it only serves as a complement to general economics. Similarly, for an anomaly to violate market efficiency, an investor must be able to trade against it and earn abnormal profits; this is not the case for many anomalies.[79] A specific example of this criticism appears in some explanations of the equity premium puzzle.[80] It is argued that the cause is entry barriers (both practical and psychological) and that the equity premium should reduce as electronic resources open up the stock market to more traders.[81] In response, others contend that most personal investment funds are managed through superannuation funds, minimizing the effect of these putative entry barriers.[82] In addition, professional investors and fund managers seem to hold more bonds than one would expect given return differentials.[83]

Quantitative behavioral finance

[edit]Quantitative behavioral finance uses mathematical and statistical methodology to understand behavioral biases. Some financial models used in money management and asset valuation, as well as more theoretical models, likewise, incorporate behavioral finance parameters. Examples:

- Thaler's model of price reactions to information, with three phases (underreaction, adjustment, and overreaction), creating a price trend. (One characteristic of overreaction is that average returns following announcements of good news is lower than following bad news. In other words, overreaction occurs if the market reacts too strongly or for too long to news, thus requiring an adjustment in the opposite direction. As a result, outperforming assets in one period is likely to underperform in the following period. This also applies to customers' irrational purchasing habits.[84])

- The stock image coefficient

- Artificial financial market

- Market microstructure

Applied issues

[edit]Behavioral game theory

[edit]Behavioral game theory, invented by Colin Camerer, analyzes interactive strategic decisions and behavior using the methods of game theory,[85] experimental economics, and experimental psychology. Experiments include testing deviations from typical simplifications of economic theory such as the independence axiom[86] and neglect of altruism,[87] fairness,[88] and framing effects.[89] On the positive side, the method has been applied to interactive learning[90] and social preferences.[91][92][93] As a research program, the subject is a development of the last three decades.[94][95][96][97][98][99][100]

Artificial intelligence

[edit]Much of the decisions are more and more made either by human beings with the assistance of artificial intelligent machines or wholly made by these machines. Tshilidzi Marwala and Evan Hurwitz in their book,[101] studied the utility of behavioral economics in such situations and concluded that these intelligent machines reduce the impact of bounded rational decision making. In particular, they observed that these intelligent machines reduce the degree of information asymmetry in the market, improve decision making and thus making markets more rational.

The use of AI machines in the market in applications such as online trading and decision making has changed major economic theories.[101] Other theories where AI has had impact include in rational choice, rational expectations, game theory, Lewis turning point, portfolio optimization and counterfactual thinking.

Other areas of research

[edit]Other branches of behavioral economics enrich the model of the utility function without implying inconsistency in preferences. Ernst Fehr, Armin Falk, and Rabin studied fairness, inequity aversion and reciprocal altruism, weakening the neoclassical assumption of perfect selfishness. This work is particularly applicable to wage setting. The work on "intrinsic motivation by Uri Gneezy and Aldo Rustichini and "identity" by George Akerlof and Rachel Kranton assumes that agents derive utility from adopting personal and social norms in addition to conditional expected utility. According to Aggarwal, in addition to behavioral deviations from rational equilibrium, markets are also likely to suffer from lagged responses, search costs, externalities of the commons, and other frictions making it difficult to disentangle behavioral effects in market behavior.[102]

"Conditional expected utility" is a form of reasoning where the individual has an illusion of control, and calculates the probabilities of external events and hence their utility as a function of their own action, even when they have no causal ability to affect those external events.[103][104]

Behavioral economics caught on among the general public with the success of books such as Dan Ariely's Predictably Irrational. Practitioners of the discipline have studied quasi-public policy topics such as broadband mapping.[105][106]

Applications for behavioral economics include the modeling of the consumer decision-making process for applications in artificial intelligence and machine learning. The Silicon Valley–based start-up Singularities is using the AGM postulates proposed by Alchourrón, Gärdenfors, and Makinson—the formalization of the concepts of beliefs and change for rational entities—in a symbolic logic to create a "machine learning and deduction engine that uses the latest data science and big data algorithms in order to generate the content and conditional rules (counterfactuals) that capture customer's behaviors and beliefs."[107]

The University of Pennsylvania's Center for Health Incentives & Behavioral Economics (CHIBE) looks at how behavioral economics can improve health outcomes. CHIBE researchers have found evidence that many behavioral economics principles (incentives, patient and clinician nudges, gamification, loss aversion, and more) can be helpful to encourage vaccine uptake, smoking cessation, medication adherence, and physical activity, for example.[108]

Applications of behavioral economics also exist in other disciplines, for example in the area of supply chain management.[109]

Honors and awards

[edit]Nobel Prize

[edit]1978 – Herbert Simon

[edit]In 1978 Herbert Simon was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences "for his pioneering research into the decision-making process within economic organizations".[110] Simon earned his Bachelor of Arts and his Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Chicago before going on to teach at Carnegie Tech.[111] Herbert was praised for his work on bounded rationality, a challenge to the assumption that humans are rational actors.[112]

2002 –- Daniel Kahneman and Vernon L. Smith

[edit]In 2002, psychologist Daniel Kahneman and economist Vernon L. Smith were awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. Kahneman was awarded the prize "for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty", while Smith was awarded the prize "for having established laboratory experiments as a tool in empirical economic analysis, especially in the study of alternative market mechanisms."[113]

2017 – Richard Thaler

[edit]In 2017, economist Richard Thaler was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for "his contributions to behavioral economics and his pioneering work in establishing that people are predictably irrational in ways that defy economic theory."[114][115] Thaler was especially recognized for presenting inconsistencies in standard Economic theory and for his formulation of mental accounting and Libertarian paternalism[116][117]

Other Awards

[edit]1999 – Andrei Shleifer

[edit]The work of Andrei Shleifer focused on behavioral finance and made observations on the limits of the efficient market hypothesis.[7] Shleifer received the 1999 John Bates Clark Medal from the American Economic Association for his work.[118]

2001 – Matthew Rabin

[edit]Matthew Rabin received the "genius" award from the MarArthur Foundation in 2000.[7] The American Economic Association chose Rabin as the recipient of the 2001 John Bates Clark medal. Rabin's awards were given to him primarily on the basis of his work on fairness and reciprocity, and on present bias.[119]

2003 – Sendhil Mullainathan

[edit]Sendhil Mullainathan was the youngest of the chosen MacArthur Fellows in 2002, receiving a fellowship grant of $500,000 in 2003.[120][7] Mullainathan was praised by the MacArthur Foundation as working on economics and psychology as an aggregate.[7] Mullainathan's research focused on the salaries of executives on Wall Street; he also has looked at the implications of racial discrimination in markets in the United States.[121][7]

Criticism

[edit]Taken together, two landmark papers in economic theory which were published before the field of Behavioral Economics emerged, the first is the paper "Uncertainty, Evolution, and Economic Theory" by Armen Alchian from 1950 and the second is the paper "Irrational Behavior and Economic Theory" from 1962 by Gary Becker, both of which were published in the Journal of Political Economy,[122][123] provide a justification for standard neoclassical economic analysis. Alchian's 1950 paper uses the logic of natural selection, the Evolutionary Landscape model, stochastic processes, probability theory, and several other lines of reasoning to justify many of the results derived from standard supply analysis assuming firms which maximizing their profits, are certain about the future, and have accurate foresight without having to assume any of those things. Becker's 1962 paper shows that downward sloping market demand curves (the most important implication of the law of demand) do not actually require an assumption that the consumers in that market are rational, as is claimed by behavioral economists and they also follow from a wide variety of irrational behavior as well.

The lines of reasoning and argumentation used in these two papers is re-expressed and expanded upon in (at least) one other professional economic publication for each of them. As for Alchian's evolutionary economics via natural selection by way of environmental adoption thesis, it is summarized, followed by an explicit exploration of its theoretical implications for Behavioral Economic theory, then illustrated via examples in several different industries including banking, hospitality, and transportation, in the 2014 paper "Uncertainty, Evolution, and Behavioral Economic Theory," by Manne and Zywicki.[124] And the argument made in Becker's 1962 paper, that a 'pure' increase in the (relative) price (or terms of trade) of good X must reduce the amount of X demanded in the market for good X, is explained in greater detail in chapters (or as he calls them, "Lectures" because this textbook is more or less a transcription of his lectures given in his Price Theory course taught to 1st year PhD students several years earlier) 4 (called The Opportunity Set) and 5 (called Substitution Effects) of Gary Becker's graduate level textbook Economic Theory, originally published in 1971.[125]

Besides the three critical aforementioned articles, critics of behavioral economics typically stress the rationality of economic agents.[126] A fundamental critique is provided by Maialeh (2019) who argues that no behavioral research can establish an economic theory. Examples provided on this account include pillars of behavioral economics such as satisficing behavior or prospect theory, which are confronted from the neoclassical perspective of utility maximization and expected utility theory respectively. The author shows that behavioral findings are hardly generalizable and that they do not disprove typical mainstream axioms related to rational behavior.[127]

Others, such as the essayist and former trader Nassim Taleb note that cognitive theories, such as prospect theory, are models of decision-making, not generalized economic behavior, and are only applicable to the sort of once-off decision problems presented to experiment participants or survey respondents.[128] It is noteworthy that in the episode of EconTalk in which Taleb said this, he and the host, Russ Roberts discuss the significance of Gary Becker's 1962 paper cited in the first paragraph in this section as an argument against any implications which can be drawn from one shot psychological experiments on market level outcomes outside of laboratory settings, i.e. in the real world. Others argue that decision-making models, such as the endowment effect theory, that have been widely accepted by behavioral economists may be erroneously established as a consequence of poor experimental design practices that do not adequately control subject misconceptions.[2][129][130][131]

Despite a great deal of rhetoric, no unified behavioral theory has yet been espoused: behavioral economists have proposed no alternative unified theory of their own to replace neoclassical economics with.

David Gal has argued that many of these issues stem from behavioral economics being too concerned with understanding how behavior deviates from standard economic models rather than with understanding why people behave the way they do. Understanding why behavior occurs is necessary for the creation of generalizable knowledge, the goal of science. He has referred to behavioral economics as a "triumph of marketing" and particularly cited the example of loss aversion.[132]

Traditional economists are skeptical of the experimental and survey-based techniques that behavioral economics uses extensively. Economists typically stress revealed preferences over stated preferences (from surveys) in the determination of economic value. Experiments and surveys are at risk of systemic biases, strategic behavior and lack of incentive compatibility. Some researchers point out that participants of experiments conducted by behavioral economists are not representative enough and drawing broad conclusions on the basis of such experiments is not possible. An acronym WEIRD has been coined in order to describe the studies participants—as those who come from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic societies.[133]

Responses

[edit]Matthew Rabin[134] dismisses these criticisms, countering that consistent results typically are obtained in multiple situations and geographies and can produce good theoretical insight. Behavioral economists, however, responded to these criticisms by focusing on field studies rather than lab experiments. Some economists see a fundamental schism between experimental economics and behavioral economics, but prominent behavioral and experimental economists tend to share techniques and approaches in answering common questions. For example, behavioral economists are investigating neuroeconomics, which is entirely experimental and has not been verified in the field.[citation needed]

The epistemological, ontological, and methodological components of behavioral economics are increasingly debated, in particular by historians of economics and economic methodologists.[135]

According to some researchers,[136] when studying the mechanisms that form the basis of decision-making, especially financial decision-making, it is necessary to recognize that most decisions are made under stress[137] because, "Stress is the nonspecific body response to any demands presented to it."[138]

Related fields

[edit]Experimental economics

[edit]Experimental economics is the application of experimental methods, including statistical, econometric, and computational,[139] to study economic questions. Data collected in experiments are used to estimate effect size, test the validity of economic theories, and illuminate market mechanisms. Economic experiments usually use cash to motivate subjects, in order to mimic real-world incentives. Experiments are used to help understand how and why markets and other exchange systems function as they do. Experimental economics have also expanded to understand institutions and the law (experimental law and economics).[140]

A fundamental aspect of the subject is design of experiments. Experiments may be conducted in the field or in laboratory settings, whether of individual or group behavior.[141]

Variants of the subject outside such formal confines include natural and quasi-natural experiments.[142]

Neuroeconomics

[edit]Neuroeconomics is an interdisciplinary field that seeks to explain human decision making, the ability to process multiple alternatives and to follow a course of action. It studies how economic behavior can shape our understanding of the brain, and how neuroscientific discoveries can constrain and guide models of economics.[143] It combines research methods from neuroscience, experimental and behavioral economics, and cognitive and social psychology.[144] As research into decision-making behavior becomes increasingly computational, it has also incorporated new approaches from theoretical biology, computer science, and mathematics.

Neuroeconomics studies decision making by using a combination of tools from these fields so as to avoid the shortcomings that arise from a single-perspective approach. In mainstream economics, expected utility (EU) and the concept of rational agents are still being used. Many economic behaviors are not fully explained by these models, such as heuristics and framing.[145] Behavioral economics emerged to account for these anomalies by integrating social, cognitive, and emotional factors in understanding economic decisions. Neuroeconomics adds another layer by using neuroscientific methods in understanding the interplay between economic behavior and neural mechanisms. By using tools from various fields, some scholars claim that neuroeconomics offers a more integrative way of understanding decision making.[143]

Evolutionary psychology

[edit]An evolutionary psychology perspective states that many of the perceived limitations in rational choice can be explained as being rational in the context of maximizing biological fitness in the ancestral environment, but not necessarily in the current one. Thus, when living at subsistence level where a reduction of resources may result in death, it may have been rational to place a greater value on preventing losses than on obtaining gains. It may also explain behavioral differences between groups, such as males being less risk-averse than females since males have more variable reproductive success than females. While unsuccessful risk-seeking may limit reproductive success for both sexes, males may potentially increase their reproductive success from successful risk-seeking much more than females can.[146]

Notable people

[edit]Economics

[edit]- George Akerlof

- Werner De Bondt

- Paul De Grauwe[147]

- Linda C. Babcock

- Douglas Bernheim[148]

- Colin Camerer

- Armin Falk

- Urs Fischbacher

- Tshilidzi Marwala

- Susan E. Mayer

- Ernst Fehr

- Simon Gächter

- Uri Gneezy[149]

- David Laibson

- Louis Lévy-Garboua

- John A. List

- George Loewenstein

- Sendhil Mullainathan

- John Quiggin

- Matthew Rabin

- Reinhard Selten

- Herbert A. Simon

- Vernon L. Smith

- Robert Sugden[150]

- Larry Summers

- Richard Thaler

- Abhijit Banerjee

- Esther Duflo

- Kevin Volpp

- Katy Milkman

Finance

[edit]Psychology

[edit]See also

[edit]- Adaptive market hypothesis

- Animal Spirits (Keynes)

- Behavioralism

- Behavioral operations research

- Behavioral Strategy

- Big Five personality traits

- Confirmation bias

- Cultural economics

- Culture change

- Economic sociology

- Emotional bias

- Fuzzy-trace theory

- Hindsight bias

- Homo reciprocans

- Important publications in behavioral economics

- List of cognitive biases

- Methodological individualism

- Nudge theory

- Observational techniques

- Praxeology

- Priority heuristic

- Regret theory

- Repugnancy costs

- Socioeconomics

- Socionomics

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Lin, Tom C. W. (April 16, 2012). "A Behavioral Framework for Securities Risk". Seattle University Law Review. SSRN. SSRN 2040946.

- ^ a b Zeiler, Kathryn; Teitelbaum, Joshua (March 30, 2018). "Research Handbook on Behavioral Law and Economics". Books.

- ^ "Search of behavioural economics". in Palgrave

- ^ Minton, Elizabeth A.; Kahle, Lynn R. (2013). Belief Systems, Religion, and Behavioral Economics: Marketing in Multicultural Environments. Business Expert Press. ISBN 978-1-60649-704-3.

- ^ Ashraf, Nava; Camerer, Colin F.; Loewenstein, George (2005). "Adam Smith, Behavioral Economist". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 19 (3): 131–45. doi:10.1257/089533005774357897.

- ^ a b c d e Agner, Erik (2021). A course in Behavioral Economics (3rd ed.). Red Globe Press. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-1-352-01080-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Sent, Esther-Mirjam (2004). "Behavioral Economics: How Psychology Made Its (Limited) Way Back into Economics". History of Political Economy. 36 (4): 735–760. doi:10.1215/00182702-36-4-735. hdl:2066/67175. ISSN 1527-1919. S2CID 143911190 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ a b c d e Geiger, Niels (2017). "The Rise of Behavioral Economics: A Quantitative Assessment". Social Science History. 41 (3): 555–583. doi:10.1017/ssh.2017.17. ISSN 0145-5532. S2CID 56373713.

- ^ a b c d e f g Camerer, Colin; Loewenstein, George; Rabin, Matthew (2004). Advances in Behavioral Economics. Princeton University Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 9780691116822.

- ^ Hansen, Kristian Bondo; Presskorn-Thygesen, Thomas (July 2022). "On Some Antecedents of Behavioural Economics". History of the Human Sciences. 35 (3–4): 58–83. doi:10.1177/09526951211000950. S2CID 234860041.

- ^ Brown, Stephen J.; Goetzmann, William N.; Kumar, Alok (January 1998). "The Dow Theory: William Peter Hamilton's Track Record Reconsidered". The Journal of Finance. 53 (4): 1311–1333. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00054. JSTOR 117403.

- ^ a b Boyd, Richard (Summer 2020). "The Early Modern Origins of Behavioral Economics". Social Philosophy & Policy. 37 (1). Oxford: Cambridge University Press: 30–54. doi:10.1017/S0265052520000035. S2CID 230794629.

- ^ "What is behavioral economics? | University of Chicago News". news.uchicago.edu. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ Camerer, Colin (September 14, 1999). "Behavioral economics: Reunifying psychology and economics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (19): 10575–10577. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9610575C. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.19.10575. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 33745. PMID 10485865.

- ^ "Ward Edward Papers". Archival Collections. Archived from the original on April 16, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- ^ Luce 2000.

- ^ a b Gigerenzer, Gerd; Selten, Reinhard (2002). Bounded Rationality: The Adaptive Toolbox. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-57164-7.

- ^ Cyert, Richard; March, James G. (1963). A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

- ^ Sent, E.M. (2004). "Behavioral economics: How psychology made its (limited) way back into economics". History of Political Economy. 36 (4): 735–760. doi:10.1215/00182702-36-4-735. hdl:2066/67175. S2CID 143911190.

- ^ Thaler, Richard H.; Sunstein, Cass R. (April 8, 2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-14-311526-7. OCLC 791403664.

- ^ Thaler, Richard H.; Sunstein, Cass R.; Balz, John P. (April 2, 2010). Choice Architecture. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1583509. S2CID 219382170. SSRN 1583509.

- ^ Wright, Joshua; Ginsberg, Douglas (February 16, 2012). "Free to Err?: Behavioral Law and Economics and its Implications for Liberty". Library of Law & Liberty.

- ^ Sunstein, Cass (2009). Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199793143.

- ^ Kahneman & Diener 2003.

- ^ a b Tversky, Amos; Kahneman, Daniel (1992). "Advances in Prospect Theory: Cumulative Representation of Uncertaintly". Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 5 (4): 297–323. doi:10.1007/BF00122574. ISSN 0895-5646. S2CID 8456150.Abstract.

- ^ Hogarth & Reder 1987.

- ^ "Nobel Laureates 2002". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- ^ Simon, Herbert (1990). Utility and Probability. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-349-20568-4.

- ^ Kahneman, Daniel (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 22. ISBN 978-0374275631.

- ^ a b "What is behavioral economics? | University of Chicago News". news.uchicago.edu. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ Wilk, J. (1999), "Mind, Nature and the Emerging Science of Change: An Introduction to Metamorphology", in G. Cornelis; S. Smets; J. Van Bendegem (eds.), Metadebates on Science, vol. 6, Springer Netherlands, pp. 71–87, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-2245-2_6, ISBN 978-90-481-5242-1

- ^ O'Hanlon, B.; Wilk, J. (1987), Shifting contexts : The generation of effective psychotherapy., New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press.

- ^ See: Dr. Jennifer Lunt and Malcolm Staves Archived 2012-04-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Andrew Sparrow (August 22, 2008). "Speak 'Nudge': The 10 key phrases from David Cameron's favorite book". The Guardian. London. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ Thaler, Richard; Sunstein, Cass (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Yale University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-14-311526-7.

- ^ Campbell-Arvai, V; Arvai, J.; Kalof, L. (2014). "Motivating sustainable food choices: the role of nudges, value orientation, and information provision". Environment and Behavior. 46 (4): 453–475. doi:10.1177/0013916512469099. S2CID 143673378.

- ^ Kroese, F.; Marchiori, D.; de Ridder, D. (2016). "Nudging healthy food choices: a field experiment at the train station" (PDF). Journal of Public Health. 38 (2): e133–7. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdv096. PMID 26186924.

- ^ Carol Lewis (July 22, 2009). "Why Barack Obama and David Cameron are keen to 'nudge' you". The Times. London. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ James Forsyth (July 16, 2009). "Nudge, nudge: meet the Cameroons' new guru". The Spectator. Archived from the original on January 24, 2009. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ "Who we are". The Behavioural Insights Team.

- ^ Marsh, Tim (January 2012). "Cast No Shadow" (PDF). Rydermarsh.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2017.

- ^ Sunstein, Cass R. (August 24, 2016). The Ethics of Influence: Government in the Age of Behavioral Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-14070-7.

- ^ Schubert, Christian (October 12, 2015). On the Ethics of Public Nudging: Autonomy and Agency (unpublished manuscript). Rochester, NY. SSRN 2672970.

- ^ Barton, Adrien; Grüne-Yanoff, Till (September 1, 2015). "From Libertarian Paternalism to Nudging—and Beyond". Review of Philosophy and Psychology. 6 (3): 341–359. doi:10.1007/s13164-015-0268-x. ISSN 1878-5158.

- ^ Bovens, Luc (2009). "The Ethics of Nudge". Preference Change. Theory and Decision Library. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 207–219. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2593-7_10. ISBN 9789048125920. S2CID 141283500.

- ^ Goodwin, Tom (June 1, 2012). "Why We Should Reject 'Nudge'". Politics. 32 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9256.2012.01430.x. ISSN 0263-3957. S2CID 153597777.

- ^ Yeung, Karen (January 1, 2012). "Nudge as Fudge". The Modern Law Review. 75 (1): 122–148. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2230.2012.00893.x. ISSN 1468-2230.

- ^ Hausman, Daniel M.; Welch, Brynn (March 1, 2010). "Debate: To Nudge or Not to Nudge*". Journal of Political Philosophy. 18 (1): 123–136. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00351.x. ISSN 1467-9760.

- ^ Lepenies, Robert; Małecka, Magdalena (September 1, 2015). "The Institutional Consequences of Nudging – Nudges, Politics, and the Law". Review of Philosophy and Psychology. 6 (3): 427–437. doi:10.1007/s13164-015-0243-6. ISSN 1878-5158. S2CID 144157454.

- ^ Alemanno, A.; Spina, A. (April 1, 2014). "Nudging legally: On the checks and balances of behavioral regulation". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 12 (2): 429–456. doi:10.1093/icon/mou033. ISSN 1474-2640.

- ^ Kemmerer, Alexandra; Möllers, Christoph; Steinbeis, Maximilian; Wagner, Gerhard (July 15, 2016). Choice Architecture in Democracies: Exploring the Legitimacy of Nudging - Preface. Rochester, NY: Hart Publishing. SSRN 2810229.

- ^ Sugden, Robert (June 1, 2017). "Do people really want to be nudged towards healthy lifestyles?". International Review of Economics. 64 (2): 113–123. doi:10.1007/s12232-016-0264-1. ISSN 1865-1704.

- ^ Cass R. Sunstein. "NUDGING AND CHOICE ARCHITECTURE: ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS" (PDF). Law.harvard.edu. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ^ "A nudge in the right direction? How we can harness behavioural economics". ABC News. December 1, 2015.

- ^ MÉREI, Ferenc (1987). "A perem-helyzet egyik változata: a szociálpszichológiai kontúr" [A variant of the edge-position: the contour social psychological]. Pszichológia (in Hungarian). 1: 1–5.

- ^ Garai, Laszlo (2017). "The Double-Storied Structure of Social Identity". Reconsidering Identity Economics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-52561-1.

- ^ Tversky, A (May 16, 2023). "Elimination by aspects: A theory of choice".

- ^ behavioralecon. "Mental accounting". BehavioralEconomics.com | The BE Hub. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "Anchoring Bias - Definition, Overview and Examples". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Cartwright, Edward (2018). Behavioral economics (Third ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 9781138097117.

- ^ O'Donoghue, Ted, and Matthew Rabin. 2015. "Present Bias: Lessons Learned and to Be Learned." American Economic Review, 105 (5): 273-79.

- ^ Cartwright, Edward (2018). Behavioral economics (Third ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor & Francis Group. p. 216. ISBN 9781138097117.

- ^ Croson, Rachel; Sundali, James (May 1, 2005). "The Gambler's Fallacy and the Hot Hand: Empirical Data from Casinos". Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 30 (3): 195–209. doi:10.1007/s11166-005-1153-2. ISSN 1573-0476.

- ^ Cartwright, Edward (2018). Behavioral economics (Third ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 217. ISBN 9781138097117.

- ^ Yesudian, R. I.; Yesudian, P. D. (November 27, 2020). "Case reports and narrative fallacies: the enigma of black swans in dermatology". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 46 (4): 641–645. doi:10.1111/ced.14504. PMID 33245798. S2CID 227191908.

- ^ "Narrative Fallacy - Definition, Overview and Examples in Finance". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ Cartwright, Edward (2018). Behavioral economics (Third ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 9781138097117.

- ^ Kenton, Will. "Behavioral Finance Definition". Investopedia. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "Use Cognitive Biases to Your Advantage, Institute for Management Consultants, #721, December 19, 2011". Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ Cartwright, Edward (2018). Behavioral economics (Third ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 213. ISBN 9781138097117.

- ^ "10 cognitive biases that can lead to investment mistakes". Magellan Financial Group. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Dean, M. (2017). "Limited attention and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Theory pp93-127". Journal of Economic Theory. 169 (C): 93–127. doi:10.1016/j.jet.2017.01.009. hdl:10419/145423.

- ^ "The Endowment Effect".

- ^ Glaser, Markus and Weber, Martin and Noeth, Markus. (2004). "Behavioral Finance", pp. 527-546 in Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making, Blackwell Publishers ISBN 978-1-405-10746-4

- ^ "Behavioral Finance - Overview, Examples and Guide". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Van Loo, Rory (April 1, 2015). "Helping Buyers Beware: The Need for Supervision of Big Retail". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 163 (5): 1311.

- ^ "Harry Markowitz's Modern Portfolio Theory [The Efficient Frontier]". Guided Choice. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Ricciardi, Victor (January 2000). "What is Behavioral Finance?". Business, Education & Technology Journal: 181.

- ^ "Fama on Market Efficiency in a Volatile Market". Archived from the original on March 24, 2010.

- ^ Kenton, Will. "Equity Premium Puzzle (EPP)". Investopedia. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ See Freeman, 2004 for a review

- ^ Woo, Kai-Yin; Mai, Chulin; McAleer, Michael; Wong, Wing-Keung (March 2020). "Review on Efficiency and Anomalies in Stock Markets". Economies. 8 (1): 20. doi:10.3390/economies8010020. hdl:10419/257069.

- ^ "U.S. Equity Market Structure: Making Our Markets Work Better for Investors". www.sec.gov. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Tang, David (May 6, 2013). "Why People Won't Buy Your Product Even Though It's Awesome". Flevy. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- ^ Auman, Robert. "Game Theory". in Palgrave

- ^ Camerer, Colin; Ho, Teck-Hua (March 1994). "Violations of the betweenness axiom and nonlinearity in probability". Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 8 (2): 167–96. doi:10.1007/bf01065371. S2CID 121396120.

- ^ Andreoni, James; et al. "Altruism in experiments". in Palgrave

- ^ Young, H. Peyton. "Social norms". in Palgrave

- ^ Camerer, Colin (1997). "Progress in behavioral game theory". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 11 (4): 172. doi:10.1257/jep.11.4.167. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2014. Pdf version. Archived May 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ho, Teck H. (2008). "Individual learning in games". in Palgrave

- ^ Dufwenberg, Martin; Kirchsteiger, Georg (2004). "A Theory of Sequential reciprocity". Games and Economic Behavior. 47 (2): 268–98. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.124.9311. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2003.06.003. S2CID 2508835.

- ^ Gul, Faruk (2008). "Behavioural economics and game theory". in Palgrave

- ^ Camerer, Colin F. (2008). "Behavioral game theory". in Palgrave

- ^ Camerer, Colin (2003). Behavioral game theory: experiments in strategic interaction. New York, New York Princeton, New Jersey: Russell Sage Foundation Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09039-9.

- ^ Loewenstein, George; Rabin, Matthew (2003). Advances in Behavioral Economics 1986–2003 papers. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Fudenberg, Drew (2006). "Advancing Beyond Advances in Behavioral Economics". Journal of Economic Literature. 44 (3): 694–711. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1010.3674. doi:10.1257/jel.44.3.694. JSTOR 30032349. S2CID 3490729.

- ^ Crawford, Vincent P. (1997). "Theory and Experiment in the Analysis of Strategic Interaction" (PDF). In Kreps, David M.; Wallis, Kenneth F (eds.). Advances in Economics and Econometrics: Theory and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 206–42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.298.3116. doi:10.1017/CCOL521580110.007. ISBN 9781139052009.

- ^ Shubik, Martin (2002). "Chapter 62 Game theory and experimental gaming". In Aumann and, R.; Hart, S. (eds.). Game Theory and Experimental Gaming. Handbook of Game Theory with Economic Applications. Vol. 3. Elsevier. pp. 2327–51. doi:10.1016/S1574-0005(02)03025-4. ISBN 9780444894281.

- ^ Plott, Charles R.; Smith, Vernon l (2002). "45–66". In Aumann and, R.; Hart, S. (eds.). Game Theory and Experimental Gaming#Handbook of Game Theory with Economic Applications. Handbook of Experimental Economics Results. Vol. 4. Elsevier. pp. 387–615. doi:10.1016/S1574-0722(07)00121-7. ISBN 978-0-444-82642-8.

- ^ Games and Economic Behavior (journal), Elsevier. Online

- ^ a b Marwala, Tshilidzi; Hurwitz, Evan (2017). Artificial Intelligence and Economic Theory: Skynet in the Market. London: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-66104-9.

- ^ Aggarwal, Raj (2014). "Animal Spirits in Financial Economics: A Review of Deviations from Economic Rationality". International Review of Financial Analysis. 32 (1): 179–87. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2013.07.018.

- ^ Grafstein R (1995). "Rationality as Conditional Expected Utility Maximization". Political Psychology. 16 (1): 63–80. doi:10.2307/3791450. JSTOR 3791450.

- ^ Shafir E, Tversky A (1992). "Thinking through uncertainty: nonconsequential reasoning and choice". Cognitive Psychology. 24 (4): 449–74. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(92)90015-T. PMID 1473331. S2CID 29570235.

- ^ "US National Broadband Plan: good in theory". Telco 2.0. March 17, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

... Sara Wedeman's awful experience with this is instructive....

- ^ Cook, Gordon; Wedeman, Sara (July 1, 2009). "Connectivity, the Five Freedoms, and Prosperity". Community Broadband Networks. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ "Singularities Our Company". Singular Me, LLC. 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

... machine learning and deduction engine that uses the latest data science and big data algorithms in order to generate the content and conditional rules (counterfactuals) that capture customer's behaviors and beliefs....

- ^ "Impact". Center for Health Initiatives and Behavioral Economics. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Schorsch, Timm; Marcus Wallenburg, Carl; Wieland, Andreas (2017). "The human factor in SCM: Introducing a meta-theory of behavioral supply chain management" (PDF). International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. 47: 238–262. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-10-2015-0268. hdl:10398/d02a90cf-5378-436e-94f3-7aa7bee3380e. S2CID 54685109.

- ^ "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 1978". NobelPrize.org.

- ^ Velupillai, K. Vela; Venkatachalam, Ragupathy (2021). "Herbert Alexander Simon: 15th June, 1916–9th February, 2001 A Life". Computational Economics. 57 (3): 795–797. doi:10.1007/s10614-018-9811-z. ISSN 0927-7099. S2CID 158617764.

- ^ Leahey, Thomas H. (2003). "Herbert A. Simon: Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, 1978". American Psychologist. 58 (9): 753–755. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.9.753. ISSN 1935-990X. PMID 14584993.

- ^ "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2002". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ^ Appelbaum, Binyamin (October 9, 2017). "Nobel in Economics is Awarded to Richard Thaler". The New York Times. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ Carrasco-Villanueva, Marco (October 18, 2017). "Richard Thaler y el auge de la Economía Conductual". Lucidez (in Spanish). Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ Earl, Peter E. (2018). "Richard H. Thaler: A Nobel Prize for Behavioural Economics". Review of Political Economy. 30 (2): 107–125. doi:10.1080/09538259.2018.1513236. S2CID 158175954.

- ^ "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2013". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ Blanchard, Olivier (2001). "In Honor of Andrei Shleifer: Winner of the John Bates Clark Medal". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 15 (1): 189–204. doi:10.1257/jep.15.1.189. ISSN 0895-3309. JSTOR 2696547.

- ^ Uchitelle, Louis (2001). "Economist Is Honored For Use Of Psychology". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Pais, Arthur J. (2002). "Economist Mullainathan is MacArthus 'Genius'". India Abroad. ISSN 0046-8932.

- ^ Lee, Felicia R. (2002). "Winners of MacArthus Grants Announced". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Alchian, Armen A. (1950). "Uncertainty, Evolution, and Economic Theory". Journal of Political Economy. 58 (3): 211–221. ISSN 0022-3808.

- ^ Becker, Gary S. (1962). "Irrational Behavior and Economic Theory". Journal of Political Economy. 70 (1): 1–13. ISSN 0022-3808.

- ^ Manne, G.; Zywicki, T. (2014). "Uncertainty, Evolution, and Behavioral Economic Theory". Journal of Law, Economics & Policy. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ Becker, Gary (2008). Economic Theory. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-202-30980-4.

- ^ Myagkov, Mikhail; Plott, Charles R. (December 1997). "Exchange Economies and Loss Exposure: Experiments Exploring Prospect Theory and Competitive Equilibria in Market Environments" (PDF). The American Economic Review. 87 (5): 801–828. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ Maialeh, Robin (2019). "Generalization of results and neoclassical rationality: unresolved controversies of behavioural economics methodology". Quality & Quantity. 53 (4): 1743–1761. doi:10.1007/s11135-019-00837-1. S2CID 126703002.

- ^ Roberts, Russ; Taleb, Nassim (March 2018). "EconTalk: Nassim Nicholas Taleb on Rationality, Risk, and Skin in the Game".

- ^ Klass, Greg; Zeiler, Kathryn (January 1, 2013). "Against Endowment Theory: Experimental Economics and Legal Scholarship". UCLA Law Review. 61 (1): 2.

- ^ Zeiler, Kathryn (January 1, 2011). "The Willingness to Pay-Willingness to Accept Gap, the 'Endowment Effect,' Subject Misconceptions, and Experimental Procedures for Eliciting Valuations: Reply". American Economic Review. 101 (2): 1012–1028. doi:10.1257/aer.101.2.1012.

- ^ Zeiler, Kathryn (January 1, 2005). "The Willingness to Pay-Willingness to Accept Gap, the 'Endowment Effect,' Subject Misconceptions, and Experimental Procedures for Eliciting Valuations". American Economic Review. 95 (3): 530–545. doi:10.1257/0002828054201387.

- ^ Gal, David (October 6, 2018). "Why Is Behavioral Economics So Popular?". The New York Times (Opinion). Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- ^ Henrich, Joseph; Heine, Steven J.; Norenzayan, Ara (2010). "The weirdest people in the world?" (PDF). Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 33 (2–3). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 61–83. doi:10.1017/s0140525x0999152x. ISSN 0140-525X. PMID 20550733. S2CID 219338876.

- ^ Rabin 1998, pp. 11–46.

- ^ Kersting, Felix; Obst, Daniel (April 10, 2016). "Behavioral Economics". Exploring Economics.

- ^ Sarapultsev, A.; Sarapultsev, P. (2014). "Novelty, Stress, and Biological Roots in Human Market Behavior". Behavioral Sciences. 4 (1): 53–69. doi:10.3390/bs4010053. PMC 4219248. PMID 25379268.

- ^ Zhukov, D.A. (2007). Biologija Povedenija, Gumoral'nye Mehanizmy [Biology of Behavior. Humoral Mechanisms]. St. Petersburg, Russia: Rech.

- ^ Selye, Hans (2013). Stress in Health and Disease. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-1-4831-9221-5.

- ^ Roth, Alvin E. (2002). "The Economist as Engineer: Game Theory, Experimentation, and Computation as Tools for Design Economics" (PDF). Econometrica. 70 (4): 1341–1378. doi:10.1111/1468-0262.00335. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 12, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- ^ See; Grechenig, K.; Nicklisch, A.; Thöni, C. (2010). "Punishment despite reasonable doubt—a public goods experiment with sanctions under uncertainty". Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. 7 (4): 847–867. doi:10.1111/j.1740-1461.2010.01197.x. S2CID 41945226.

- ^

- Vernon L. Smith, 2008a. "experimental methods in economics," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition, Abstract.

- _____, 2008b. "experimental economics," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract.

- Relevant subcategories are found at the Journal of Economic Literature classification codes at JEL: C9.

- ^ J. DiNardo, 2008. "natural experiments and quasi-natural experiments," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract.

- ^ a b "Research". Duke Institute for Brain Sciences. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ Levallois, Clement; Clithero, John A.; Wouters, Paul; Smidts, Ale; Huettel, Scott A. (2012). "Translating upwards: linking the neural and social sciences via neuroeconomics". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 13 (11): 789–797. doi:10.1038/nrn3354. ISSN 1471-003X. PMID 23034481. S2CID 436025.

- ^ Loewenstein, G.; Rick, S.; Cohen, J. (2008). "Neuroeconomics". Annual Review of Psychology. 59: 647–672. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093710. PMID 17883335.

- ^ Paul H. Rubin and C. Monica Capra. The evolutionary psychology of economics. In Roberts, S. C. (2011). Roberts, S. Craig (ed.). Applied Evolutionary Psychology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199586073.001.0001. ISBN 9780199586073.

- ^ Grauwe, Paul De; Ji, Yuemei (November 1, 2017). "Behavioural economics is also useful in macroeconomics".

- ^ Bernheim, Douglas; Rangel, Antonio (2008). "Behavioural public economics". in Palgrave

- ^ "Uri Gneezy". ucsd.edu. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ "Robert Sugden".

- ^ "Predictably Irrational". Dan Ariely. Archived from the original on March 13, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- ^ Staddon, John (2017). "6: Behavioral Economics". Scientific Method: How science works, fails to work or pretends to work. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-58689-4.

Sources

[edit]- Ainslie, G. (1975). "Specious Reward: A Behavioral /Theory of Impulsiveness and Impulse Control". Psychological Bulletin. 82 (4): 463–96. doi:10.1037/h0076860. PMID 1099599. S2CID 10279574.

- Baddeley, M. (2017). Behavioural economics: a very short introduction (Vol. 505). Oxford University Press.

- Barberis, N.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R. (1998). "A Model of Investor Sentiment". Journal of Financial Economics. 49 (3): 307–43. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(98)00027-0. S2CID 154782800. Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- Becker, Gary S. (1968). "Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach" (PDF). The Journal of Political Economy. 76 (2): 169–217. doi:10.1086/259394.

- Benartzi, Shlomo; Thaler, Richard H. (1995). "Myopic Loss Aversion and the Equity Premium Puzzle" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 110 (1): 73–92. doi:10.2307/2118511. JSTOR 2118511. S2CID 55030273.

- Cunningham, Lawrence A. (2002). "Behavioral Finance and Investor Governance". Washington & Lee Law Review. 59: 767. doi:10.2139/ssrn.255778. ISSN 1942-6658. S2CID 152538297.

- Daniel, K.; Hirshleifer, D.; Subrahmanyam, A. (1998). "Investor Psychology and Security Market Under- and Overreactions" (PDF). Journal of Finance. 53 (6): 1839–85. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00077. hdl:2027.42/73431. S2CID 32589687.

- Diamond, Peter; Vartiainen, Hannu (2012). Behavioral Economics and Its Applications. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2914-9.

- Eatwell, John; Milgate, Murray; Newman, Peter, eds. (1988). The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-935859-10-2.

- Garai, Laszlo (December 1, 2016). "Identity Economics: "An Alternative Economic Psychology"". Reconsidering Identity Economics. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 35–40. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-52561-1_3. ISBN 9781137525604.

- Genesove, David; Mayer, Christopher (March 2001). "Loss Aversion and Seller Behavior: Evidence from the Housing Market" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 116 (4): 1233–1260. doi:10.1162/003355301753265561. S2CID 154641267.

- Hens, Thorsten; Bachmann, Kremena (2008). Behavioural Finance for Private Banking. Wiley Finance Series. ISBN 978-0-470-77999-6.

- Hogarth, R. M.; Reder, M. W. (1987). Rational Choice: The Contrast between Economics and Psychology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-34857-5.

- John, K. (2015). "Behavioral indifference curves". Australasian Journal of Economics Education. 12 (2): 1–11.

- Kahneman, Daniel; Tversky, Amos (1979). "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk". Econometrica. 47 (2): 263–91. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.407.1910. doi:10.2307/1914185. JSTOR 1914185.

- Kahneman, Daniel; Diener, Ed (2003). Well-being: the foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kirkpatrick, Charles D.; Dahlquist, Julie R. (2007). Technical Analysis: The Complete Resource for Financial Market Technicians. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times Press. ISBN 978-0-13-153113-0.

- Kuran, Timur (1997). Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification. Harvard University Press. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-0-674-70758-0.

- Luce, R Duncan (2000). Utility of Gains and Losses: Measurement-theoretical and Experimental Approaches. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8058-3460-4.

- McGaughey, E. (2014), "Behavioural Economics and Labour Law", LSE Legal Studies Working Paper, no. 20/2014, SSRN 2460685

- Metcalfe, R; Dolan, P (2012). "Behavioural economics and its implications for transport". Journal of Transport Geography. 24: 503–511. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.019.

- Mullainathan, S.; Thaler, R. H. (2001). "Behavioral Economics". International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. pp. 1094–1100. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/02247-6. ISBN 9780080430768.

- Plott, Charles R.; Smith, Vernon L. (2008). Handbook of Experimental Economics Results. Vol. 1. Elsevier.

- Rabin, Matthew (1998). "Psychology and Economics" (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature. 36 (1): 11–46. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011.

- Schelling, Thomas C. (2006). Micromotives and Macrobehavior. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06977-8.

- Sent, E.M. (2004). "Behavioral economics: How psychology made its (limited) way back into economics". History of Political Economy. 36 (4): 735–760. doi:10.1215/00182702-36-4-735. hdl:2066/67175. S2CID 143911190.

- Shefrin, Hersh (2002). "Behavioral decision making, forecasting, game theory, and role-play" (PDF). International Journal of Forecasting. 18 (3): 375–382. doi:10.1016/S0169-2070(02)00021-3.

- Shleifer, Andrei (1999). Inefficient Markets: An Introduction to Behavioral Finance. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829228-9.

- Simon, Herbert A. (1987). "Behavioral Economics". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. Vol. 1. pp. 221–24.

- Thaler, Richard H (2016). "Behavioral Economics: Past, Present, and Future". American Economic Review. 106 (7): 1577–1600. doi:10.1257/aer.106.7.1577.

- Thaler, Richard H.; Mullainathan, Sendhil (2008). "Behavioral Economics". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0-86597-665-8. OCLC 237794267.

- Wheeler, Gregory (2018). "Bounded Rationality". In Edward Zalta (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

External links

[edit]- "Behavioral economics in U.S. (antitrust) scholarly papers". Le Concurrentialiste.

- The Behavioral Economics Guide

- Overview of Behavioral Finance

- The Institute of Behavioral Finance

- Stirling Behavioural Science Blog, of the Stirling Behavioural Science Centre at University of Stirling

- Society for the Advancement of Behavioural Economics

- Behavioral Economics: Past, Present, Future – Colin F. Camerer and George Loewenstein